AI and the Matter of Taste

In 2024 (So medieval times in the AI timeline) everyone was freaking about AI Large Language Models hitting the peak of utility due to the data wall. At the time, everyone was creating better and better models simply by stuffing them with more data and making the models bigger. But because AI companies mined all the good data available on the public web, many were expecting the AI bubble to pop when we maxed out on data. Cue the next breakthrough: synthetic data. AI models could simply generate their own data and use that as input to train the next model. That helped break through the data bottleneck. But we discovered another issue with synthetic data: model collapse. Models trained on too much synthetic data and recycled continuously on future models eventually degrade in something worse than the sum of its parts. Then, in late 2024, OpenAI mainstreamed a way to continue scaling the performance of LLMs – adding reasoning to their models through a process called chain of thought.

Essentially, the breakthrough here was instead of having models spit out the first thing that corresponded with whatever the user passed in as input, the model would now step back, “think” on its answer through some internal reflection in its own output, and somehow validate or verify the answer before responding to the user. You could see how this process would be an immediate improvement to models in certain areas – prior to reasoning, models were notoriously bad at things like math, counting, and so forth. By implementing a method for models to think in some sense, they can (with enough training and input data) always come to the correct answer, at least in domains where the answer is concrete and verifiable.

That’s more or less the current state of the art for AI field as it pertains to Transformers models – Labs have stopped scaling up the size of models past a certain point, and have focused on training them on reasoning using reinforcement learning. The issue with synthetic data collapse becomes less of an issue when these labs only pass in verifiably correct data into the models – you can generate a bunch of stuff, pick out the stuff that is “good” through some verification process, pass that in to train the next model, and have the next generation model output more stuff, again collecting the “good” data. and so these models become better and better in these specific reasoning domains.

However, what do you do when the answer isn’t cut and dry? Or a case where multiple answers can fit? We’re seeing the issue now with coding. It’s one step removed from a field like math, where the answer is right or wrong. One binary method of confirming correctness for a program is to see if it compiles. But that doesn’t actually let you know if the program does what you intended it to do. Right now we’re seeing state of the art models generate programs that can do amazing things with the snap of a finger, but they also end up with glaring security flaws or horrible designs that fall apart as a result.

This goes back to my point in the title – how do you fix the issue of AI models giving inconsistent answers to less structured questions? It’s a matter of taste – in order to get good answers, you need good input. You can’t just throw in the entire site data of something like Github as training data to an AI model and expect the AI model be the best model ever. There is a lot of garbage code on Github! (Mine included, lol) You need careful curation of input quality in order to expect output. That’s true of both human data and synthetic data.

Hayao Miyazaki once famously said the anime industry’s problem is that it’s “full of otaku” – creators who can’t stand looking at real humans. They’re drawing characters based on how other anime drew characters, who were drawing based on earlier anime, and so on. Each generation is one step further removed from someone who actually observed how a real person moves or talks. The same thing happened in games – the devs who made Sable explicitly said they wanted to avoid how “videogames can fall into the trap of being a little too self-referential and insular.” Meanwhile Miyamoto tells aspiring game designers to go outside. Zelda came from him getting lost in the woods as a kid, not from playing other adventure games.

What is the point of this aside? This is the parallel model collapse, but applied to culture. At the end of the day, for these models to continue to get better, we’re going to need people with increasingly good taste to filter out what goes into these models in order to get increasingly better outputs.

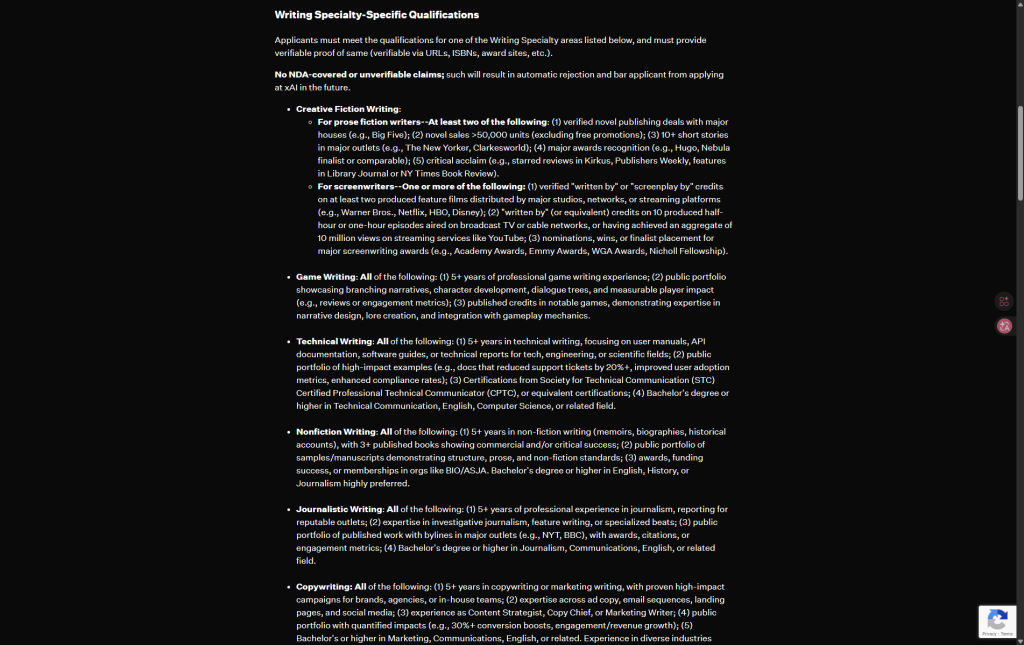

(in case that link doesn’t work, I’ve attached a screenshot: a job listing for a writer for Grok, with the minimum requirement of having released a novel under a major publisher or a won a book award or so forth)

You can just prompt models to generate a bunch of output, but diversity isn’t the same as quality. You just get more stuff – some interesting, most garbage. Someone still has to pick the good from the bad. That’s the human in the loop. And the human in the loop only works if they have some reference point outside the system they’re evaluating. Miyazaki can tell when animation looks wrong because he’s watched real people. A model trained only on its own outputs has no external reference. Neither does a creator who only consumes their own medium. (Again, not an issue for fields with verifiable answers – more of an issue the more ambiguous you go.)

Taste is just the word for a selection function that can’t be formalized. You can’t write a verification algorithm for “is this anime good” the way you can check if code compiles. The judgment has to come from somewhere outside the closed loop – and that somewhere is human experience that can’t be synthesized. Or maybe we’ll just Alpha Zero another God from the machine – who knows ¯\_(ツ)_/¯