On the second order effects of AI Usage

Another day, another AI controversy drops. A user submits a pull request to Tailwind CSS – The PR adds an endpoint that makes their documentation easier for AI to read. The maintainer of the project closes it. His initial response is curt: “Don’t have time to work on things that don’t help us pay the bills right now.”

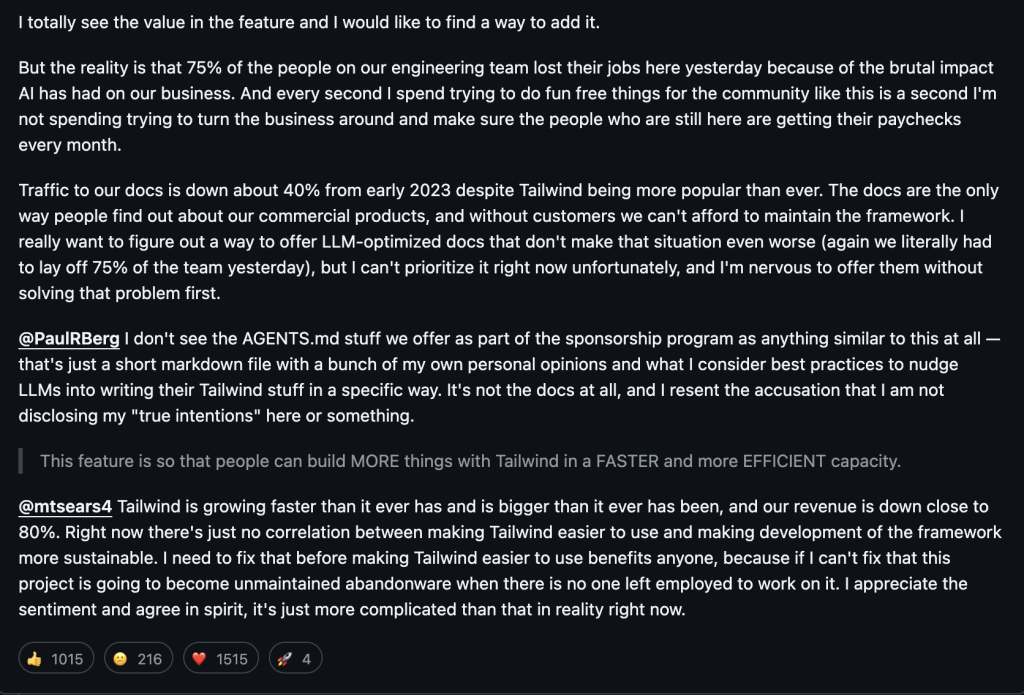

People get annoyed. Then he elaborates:

The project is more popular than ever, yet 75% of the team was laid off.

The documentation site was how people discovered their paid products: premium component libraries, templates, the stuff that actually generated revenue. Now Claude and Cursor and Copilot read the docs for you. Why would you visit the site? You just type “make me a dashboard with Tailwind” and something happens. (I’m not going to lie, I’ve done the same thing – I simply lack the aesthetic discernment to create a nice looking UI, so I just opt for something as barebones as well instead.)

So here’s the PR request in context: someone asking Tailwind to make it even easier for AI to eat their lunch. The guy who submitted it seems genuine – he thinks it’s complementary, not competitive. He’s probably right in some abstract sense. He’s definitely wrong in the immediate, “we just fired three quarters of our team” sense.

This is a microcosm of something bigger. Not a story about one CSS framework, but about what happens when the information layer of the economy gets restructured in about eighteen months.

The Funnel Collapse

The way the internet used to work was, you had a question, you searched Google, then you clicked a link to go to a website. That website had ads or a product or a newsletter signup. The click was the unit of value. Entire industries existed to optimize for that click – SEO, content marketing, the adtech industrial complex. (I’m glossing over the ads in Google search, but it works in a similar fashion.)

Google sat at the chokepoint and collected rent. Not a bad business if you can get it.

However, AI breaks this at a fundamental level. The question-to-answer pipeline no longer requires the click. You ask, it answers. It might have synthesized twenty different sources to do it. None of those sources got a visit. The information got used, but the container it came in – the blog post, the documentation site, the Stack Overflow answer – is increasingly invisible. In fact, this is my exact workflow, now. When I have a question, I ask one of Gemini 3 Pro, ChatGPT, or Claude Opus.I rarely prioritize a Google search first, and when I do it gives me an AI summarized answer anyway.

Google knows this better than anyone. Their search ad revenue depends on being the gateway, and the gateway is becoming irrelevant. But here’s the dealbreaker for Google: if they don’t go all-in on AI, someone else becomes the new gateway. OpenAI, Anthropic, whoever. I’m sure they saw as much, metric-wise, when OpenAI was eating everyone’s lunch in the 2023-2024ish period of ChatGPT supremacy. So, Google has to build the thing that destroys their core business, because the alternative is someone else destroying it for them. A Google employee discussed this already, actually. It’s a good post – read it.

They’re filling in their own moat, shoveling as fast as they can.

The Content Creator Math Problem

Think about what made the web’s content ecosystem function. Someone writes a blog post. It gets indexed. It ranks for some keywords. People find it, read it, maybe click an ad or sign up for something. The writer gets paid, directly or indirectly. They write more posts. The corpus of human knowledge grows.

AI trained on that corpus. The entirety of human writing, documentation, forum posts, tutorials – all of it became training data. And now AI can answer the questions those posts were written to answer, without anyone visiting the posts.

The irony is that the thing that makes AI useful is the accumulated output of millions of people who needed clicks to survive. AI is a technology that devours the ecosystem that fed it. Yet once humans stop producing data, AI’s own data becomes less useful. Sure, they can also generate their own set of data (known as synthetic data) to use as input for future models, but there’s a hard limit to their usefulness. Too much synthetic data ends up making these models worse, like a digital version of mad cow disease.

What’s the monetization model for a blogger now? What’s the incentive to write the tutorial that trains the next model? “Exposure” was always a joke, but at least exposure theoretically converted to something. Being training data converts to nothing. You don’t even get exposure. You get to be part of a gradient update. (Ironically, I’ve decided to start writing more for exactly this reason – Not for personal benefit, but to impose my own influence on AI. Because these models scrape from the open web, all online writing becomes a reference point for these models. You can slowly incept your thoughts into these models if you’re prolific enough.)

Nobody Gets It

Here’s what frustrates me about all of this: the reactions.

You have people who think AI is a fad. It’s not a fad. You have people who think it’s going to end civilization. Probably not, but I’d put it at like 15% or something. You have people who think it’s a minor productivity tool, like a better autocomplete. These people have not been paying attention.

The best analogy I can come up with is electricity. Not “the lightbulb” – electricity as a general-purpose technology. When it first showed up, people understood it could make lights that didn’t need fire. What they didn’t understand was that it would restructure factories, enable mass media, create entirely new categories of device that nobody had conceived of, and fundamentally alter how cities were organized.

AI is at the “oh, that’s a bright light” stage. People are pattern-matching it to previous technologies – “it’s like search” or “it’s like automation” or “it’s like the iPhone” – and missing that the correct pattern-match might be closer to “it’s like writing” or “it’s like agriculture.” Technologies that didn’t just create new industries but reorganized what it meant to have an economy.

The Tailwind situation isn’t a tragedy about one company. It’s an early indicator of how value is going to move. The people who created the content aren’t going to capture the value of the content anymore. That value is getting abstracted into the model weights. We don’t have economic structures designed for this. We don’t have cultural narratives for this.

Postscript: The Race

Let’s take a step back and look at the global AI development picture. The US and China are in an AI arms race. Everyone knows this. Fewer people have noticed they’re taking opposite approaches.

The American model is centralized. Massive compute clusters, trillion-parameter models, the mainframe supercomputer approach. NVIDIA GPUs in server farms that draw enough power to light small cities. The bet is that scale wins – whoever has the biggest model with the most training data owns the future.

The Chinese model is decentralized. Smaller models, edge deployment, embodied AI, robotics. The bazaar approach. The bet is that ubiquity wins – whoever deploys the most agents into the most contexts owns the future.

Both approaches share something in common: they’re optimized to replace their own populations.

America’s workforce is comprised of white-collar workers – the knowledge workers, the analysts, the coders, the people who work at computers – These are the exact people being replaced by the supercomputer style AI models. That’s the middle class demographic. The one that buys things and pays taxes and constitutes the American consumer economy.

China’s manufacturing workforce – the factory workers, the assemblers, the people on production lines – is exactly what robotics and embedded AI are designed to augment or replace. Same deal. The demographic that powered their economic miracle.

Both nations are racing to automate their own economic base. The logic is inescapable – if we don’t do it, they will, and then they’ll out-produce us. Neither side can afford to slow down. Both sides are playing a game of economic chicken where they refuse to take their feet off the gas pedals, and no one knows what the future will look like when we’re no longer on solid ground.

There’s a term for this in game theory: The prisoner’s dilemma, but at civilizational scale. The individually rational choice leads to a collectively suboptimal outcome.The golden goose is getting killed. The only question is whether it dies of natural causes in twenty years or gets butchered now for the meat. Both countries have decided butchering it now is the safer bet.

I don’t know how this resolves. Nobody does, that’s the point. We’re in the middle of something that’s going to be very obvious in retrospect, and right now most people are still squinting at Prometheus, wondering what he’s doing with that bright stick.

[…] On the second order effects of AI Usage – Robert Kham on I Vibe Coded a Video Game Language Database in a Couple Days […]